Overview: How can districts and schools work together to schedule tutoring into the school day?

Once you have identified the schools where tutoring will happen and selected the students who will receive it, you are ready to tackle the logistical challenge of scheduling when and where your program’s tutoring sessions will take place. While this logistical work happens primarily at the school level, districts can and should support schools to help schedule sessions effectively, particularly when changes to the master schedule require renegotiating collective bargaining agreements and making tradeoffs to ensure the success of High-Impact Tutoring.

What are best practices in scheduling?

Schedule at least three sessions per week, each one at least 30 minutes long.

For your tutoring to qualify as High-Impact Tutoring, sessions must meet this cadence and length at a minimum. While 30 minutes are sufficient for earlier grades, later grades can benefit from longer 45- to 60-minute sessions. Please see example schedules at the end of this section. For supporting research, see Research Agenda.

Build tutoring sessions into each school’s master schedule.

Tutoring during the school day is more effective than tutoring outside of the school day. Building High-Impact Tutoring into the master schedule as part of the school day ensures student attendance, strengthens school culture, and reduces the perceived stigma of tutoring. This integration of tutoring into the school day is worth it even if it means renegotiating collective bargaining agreements. Schedules reflect your priorities: if tutoring is really a priority, build it into the master schedule alongside other priorities like core instruction, social-emotional learning, or mandated services for ELLs and students with IEPs.

Never replace core instruction with tutoring.

Ensure equitable and inclusive academic support for students. If students must miss core classes to receive tutoring, they will fall behind in those classes as a result, and tutoring will have done more harm than good. Pulling students out of class can also stigmatize them and undermine their social-emotional learning. Finally, ensuring that tutoring is never a replacement for instruction can help get buy-in from teachers and their union.

Avoid scheduling models that stigmatize students receiving tutoring.

Stigma is not a significant issue if all students receive tutoring. However, if your program only targets certain students, it is essential for tutoring not to seem like a punishment. Whenever you single a student out by pulling them out of their peer group for tutoring —whether by pulling them out of class time, lunch time, or after-school free time — you reinforce the stigma associated with tutoring. Instead, consider alternative scheduling models that do not limit students’ social-emotional learning or opportunities for in-person social interaction with their peers.

Dedicate time and resources to scheduling and rescheduling.

Finding the best schedule may take some trial and error. Proposed schedules will need to be tested locally and revised at the school level. Reserve planning time for scheduling at both the district and the school level, and consider input from a diverse group of school-level stakeholders like SPED coordinators and elective teachers. Above all, ensure that stakeholders recognize that scheduling may be adjusted to reflect unforeseen circumstances like shifts in instructional modality (in-person or online) due to ongoing COVID-19 developments.

District-Level Guidance: How can districts support scheduling?

While most of the general principles above apply to school-level decisions, your district can and should provide several supports centrally to help your schools with scheduling tutoring sessions.

- Renegotiate Collective Bargaining Agreements. Collective bargaining can only happen at the district level, so renegotiating agreements is an important way districts can support schools with scheduling tutoring sessions. Because tutoring should be built into the master schedule, and because changes to the master schedule can require renegotiating collective bargaining agreements, your district should consider this possibility and be prepared to make tradeoffs to ensure the success of your new tutoring program. To make this process smoother, build stakeholder investment in High-Impact Tutoring among union leaders.

- Create District-Specific Guidelines. Review the general principles for scheduling tutoring sessions and provide schools a prioritized list of guidelines. These guidelines should also incorporate other district-wide initiatives and requirements (e.g., block scheduling for algebra, tutoring blocks must be at least 30 minutes in length, etc.).

- Create District-Specific Examples. Discuss centrally what an example tutoring schedule should look like in your district, and provide examples to schools. Concrete examples can help school leaders see how accommodating multiple priorities and rules can still allow them to achieve a common vision.

- Bring School Stakeholders in for Direct Thought Partnership. Your tutoring program’s project manager is uniquely well-positioned to help schools reflect on the effectiveness of their current schedule to ensure that what has worked in the past is incorporated into the new schedule alongside tutoring. Here are a few reflection questions for your project manager to ask when initiating those conversations:

- Reflect on current scheduling by asking schools:

- Priorities: What were the main decision factors that went into your schedule?

- Upsides: What worked well about your current schedule?

- Downsides: What challenges have there been with your current schedule?

- Student Needs: What are the most pressing student needs and how does the current schedule support or not support those needs?

- Brainstorm a new schedule by asking schools about:

- Time: How will tutoring be embedded during regular school hours to eliminate barriers to participation? How will you ensure tutoring sessions do not replace core instruction?

- Frequency: How will you ensure that each student consistently receives at least three 30-60 minute tutoring sessions a week with the same tutor?

- Modality: How will tutoring be delivered—in person, virtually, or both? How will that impact scheduling?

- Tutor Availability: Given your tutors’ work schedules, when are tutors most available?

- Reflect on current scheduling by asking schools:

- Provide Logistical Support for Middle and High Schools. In addition to facilitating direct thought partnership, you can help streamline logistics by ensuring schools have the necessary course codes for High-Impact Tutoring.

School-Level Guidance: What information is important to consider when making scheduling decisions?

Adding tutoring to your schedule involves balancing various logistical needs—which often has programming implications, since making any schedule change inevitably affects other parts of the schedule. To proactively prevent problems, schools should consider these additional factors before they begin scheduling:

- Student-Tutor Ratio. Understand how many your tutors can support at any one time and do not schedule more students for tutoring simultaneously than tutors can support. (see here for more on understanding how many tutors your program may require)

- Proctoring Needs. Determine whether any additional staff are required to be present during tutoring and take this into consideration when scheduling. Tutoring programs that do not use certified teachers as tutors will often require a teacher or staff member present to oversee the classroom while tutors are working with students.

- Space and Tech Allocation. Identify how many classrooms and/or devices or other resources (such as whiteboards) are needed for tutoring at any one time and which rooms are available during which class periods.

- Tutor Work Schedules. Determine when your tutors will be available. Coordinate with any local partner organizations (like a local university or high school, if relying on near-peer tutors) to determine schedule availability.

- Time for Collaboration. Build in time for teachers and tutors to collaborate. Scheduling this time into the school day helps teachers view tutoring as a resource that supports their core instruction.

- Mandated Services. Prioritize mandated services for ELLs and students with IEPs before scheduling tutoring. If any tutoring block is scheduled during the time typically allocated for mandated services, schools must ensure students can receive their services while also not denying them access to High-Impact Tutoring.

- Coordination with Other Initiatives. Consider other programs in order to prevent double-booking spaces or student or staff time.

School-Level Guidance: What are some common scheduling approaches?

Recommended Approaches

Finding time in the school day for tutoring may seem daunting; however, many approaches are available. Many schools prioritize certain student groups for tutoring or rotate students in and out of tutoring by semester. Here are some ways schools schedule tutoring by repurposing time that was already in their master schedules.

- Flex Blocks. Many school schedules have a consistent period that is flexibly used, such as advisory or homeroom. These periods can often be repurposed for tutoring. See more examples below.

- For High Schools: To boost attendance, avoid scheduling tutoring during your first or last period.

- For Elementary or Middle Schools: If your tutoring program model relies on high school tutors, coordinate with local high schools and align your flex blocks with their service-learning periods.

- Intervention Periods. Some schools have a staggered two-period lunch, where half the students have lunch during the first period and half have lunch during the second. Each group’s non-lunch period can then be used for tutoring. See more examples below.

- Extension Periods/Parallel Blocks. If the school uses block scheduling and core instruction has extended periods, then tutoring can occur during the second portion of the extended classes during independent practice. This setup works best when blocks are consecutive; otherwise, attendance for the tutoring block may drop.

- For Middle or High Schools: To simplify logistics, tutors can “push in” for the second block.

- For Elementary Schools: Tutoring can occur in a separate space apart from the student’s normal classroom where students from multiple classes are taken to form homogenous groups by mastery level and student need.

- Electives. For many schools, the most flexible part of their schedule is electives. While it is not recommended to replace all electives with tutoring, schools could use some elective time to provide tutoring for students. For example, students could have tutoring three or four times a week and attend their elective classes at the same time on the other days.

The following options for scheduling tutoring have equity and efficacy concerns for students. However, tutoring programs may consider these options in addition to tutoring within the school day. Students and their caregivers may also request that tutoring come in the following formats:

- Pull-Outs from Core Classes or Lunch Time. Taking students out of lunch or core classes can undermine their social-emotional learning. Pulling students out of class or away from friends during lunch time will almost always seem like a punishment, stigmatizing students who receive tutoring. If this model must be used, students should be pulled out of whichever time slot is considered the lowest opportunity cost, and never out of core instruction.

- After-School Tutoring. Attendance at after-school tutoring is much harder to guarantee, and this model forces older students to choose between attending tutoring and extra-curricular activities, caring for younger siblings or working an after-school job to help support their households. If this model must be used, schedule tutoring immediately before or after the school day and consider potential conflicts with extracurriculars. Monitor uptake and attendance closely to make sure the tutoring programs is serving students equitably.

Example Schedules

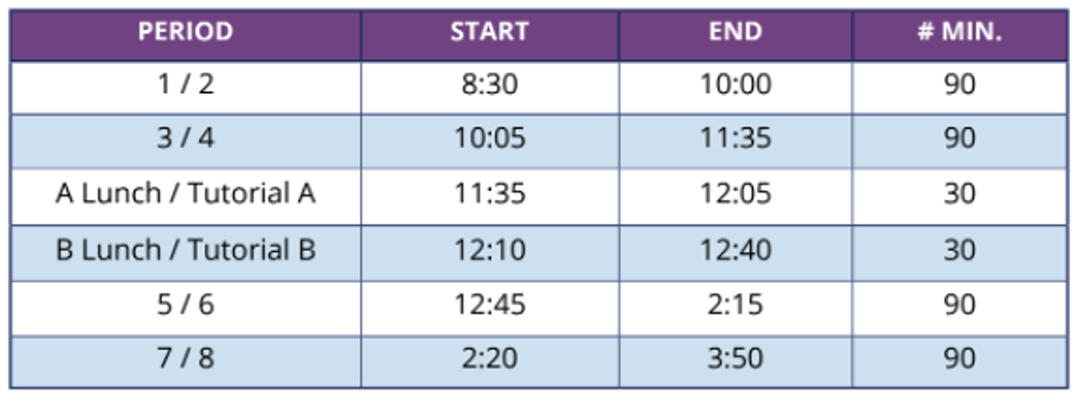

Below are some examples of creative scheduling that fits High-Impact Tutoring into a master schedule. This content is adapted from Unlocking Time, where you can find additional creative ideas for reworking your school schedule. The two options highlighted below work particularly well with tutoring.

|

Extension Periods/Parallel Blocks Description: Instruction in targeted classes is divided into two blocks of time. During the first block, all students receive whole-group instruction in their original classes. During the second block, students are regrouped into homogenous small groups led by other teachers of the same grade or content and tutors. Additionally, some groups may be independent, using personalized learning software. |

|

| Pros | Cons |

|

|

|

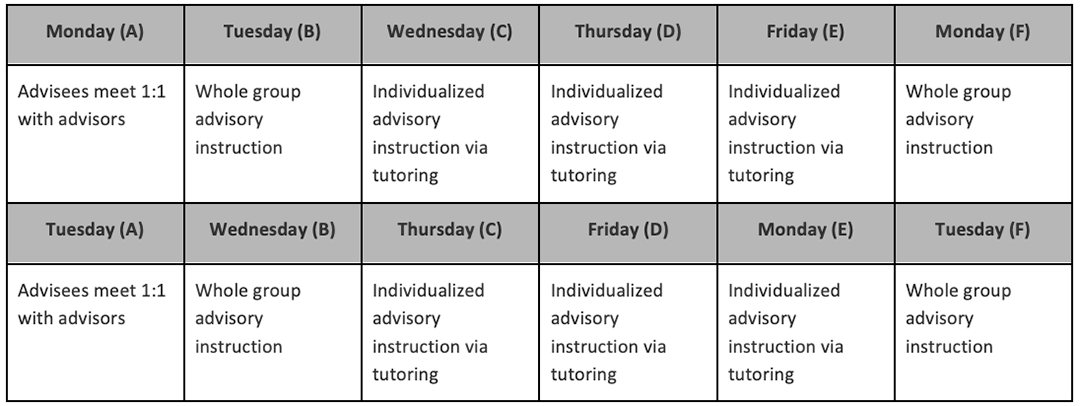

Intervention Periods/Flex Blocks Description: A new period is added to the school day where teachers assign students or students self-select into the provided tutoring options, college advisory sessions, or social-emotional learning blocks for that day. |

|

| Pros | Cons |

|

|

Variations/Examples (SOURCE: Edficiency)

|

|